The Memes Will Continue: When Power Cosplays as the Powerless

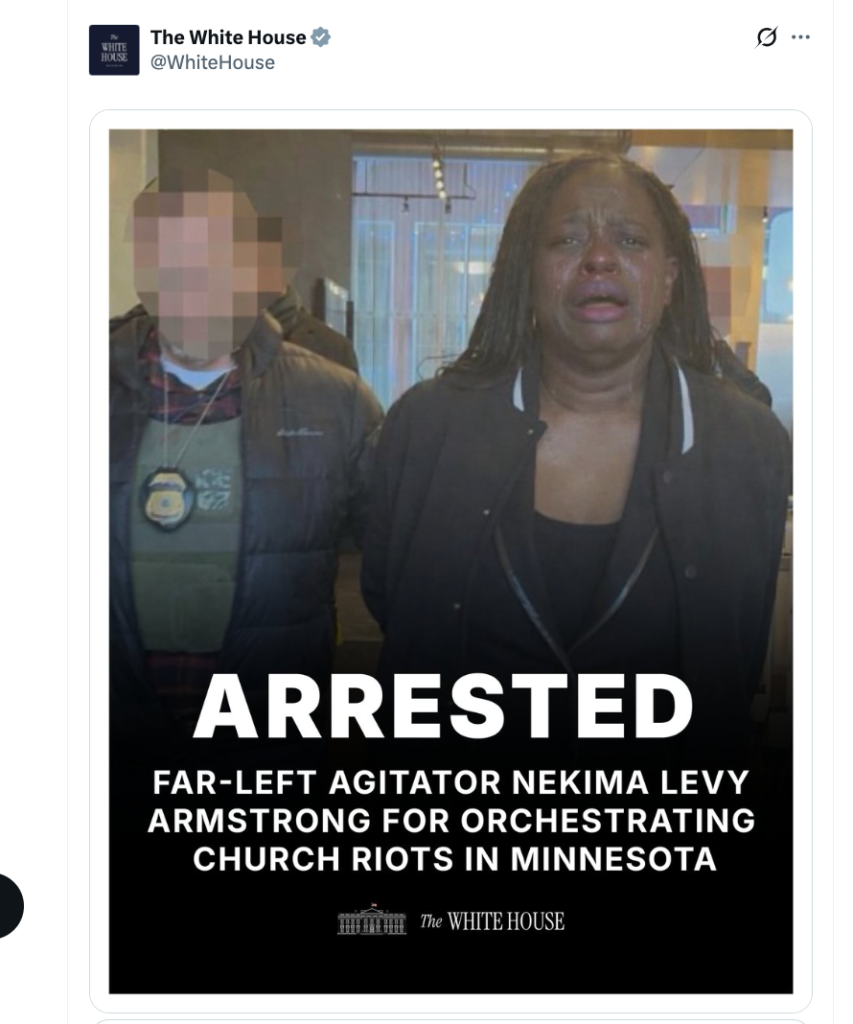

The White House did not quietly share a misleading photograph; it publicly posted a taunt. A civil rights attorney is shown being arrested in a Minnesota church, but in the official version pushed out on the president’s X account, her composed face has been rewritten into a spectacle of anguish, complete with AI‑added tears and the smirk of a meme. When critics objected, the response from the communications shop was not remorse but swagger: “the memes will continue.”

This needs to be said plainly: this is not a sophisticated deepfake engineered to fool forensics labs; it is state‑sanctioned trolling. That distinction matters, because trolling has historically been a weapon of the weak against the powerful, a way for people without tanks or television stations to bite back; here, the most powerful political office in the country is using that same grammar to punch down at a woman whose body it has already seized. The message is not “do not be deceived by AI,” as media press releases politely frame it, but “we can literally redraw your reality and then laugh about it.”

What makes this image so revealing is not the technology but the insecurity behind it. Thirty‑three minutes after Homeland Security posted the original photo of Nekima Levy Armstrong looking calm and in control, the White House produced a new version that frantically overcorrects: darker skin, wetter eyes, a gaping mouth, bold‑face labels calling her a “far‑left agitator.” You do not need to disfigure someone you genuinely believe you have defeated; you only need to humiliate the people you secretly fear might walk out of that frame, stand in front of a microphone, and start telling their own story.

If this feels familiar, it is because we have already lived through a dress rehearsal with the AI‑generated “Trump arrest” images. Those pictures were born on the margins: a Bellingcat founder amusing himself on Midjourney, posting clearly labeled fantasy shots of Trump being hauled away, which then leaked into wider circulation and briefly fooled people who were not in on the joke. In other words, the bottom of the hierarchy used synthetic imagery to play out a wish, and institutional actors and fact‑checkers responded by treating it as a literacy problem: here is how to spot a fake, here is why you should not believe everything you see.

What happened with Nekima Levy Armstrong is the mirror image of that scenario. The image did not bubble up from some anonymous account; it came down from the top, stamped with the authority of the White House, and it targeted a real woman in real time as she was being funneled into the justice system. Yet the official conversation is almost identical: journalism groups gently reminder‑email reporters to “vet all information” and “verify visuals” before sharing, as if the central scandal were sloppy newsroom workflow rather than an administration casually weaponizing AI to rewrite a citizen’s face. That is the comfort zone of media ethics: focus on whether the press is careful enough because it avoids naming the more unsettling question: what is your code worth if you will not say out loud that the problem is power humiliating the people it is supposed to serve?

Trolling is the bastard child of Saul Alinsky’s playbook, and this is where the cosplay breaks down. In Rules for Radicals, ridicule is a weapon you hand to people at the bottom of the hill, not a toy you give the people in the palace. “Ridicule is man’s most potent weapon,” Alinsky wrote, because it is hard to fight and it forces the powerful into flailing, self‑revealing overreactions. The entire point is to punch up: make the mayor, the CEO, the president look ridiculous so their aura of inevitability cracks in front of a crowd.

The contemporary Right loves to denounce Alinsky while strip‑mining his rules for aesthetic, not context. They imitate the surface elements: the sneer, the meme, the “own”, but invert the power flow, turning a tactic designed for the powerless into a state‑run humiliation machine aimed at protesters, journalists, and anyone who gets in the frame. That is why this incident feels so off: the White House is trying to LARP as the scrappy underdog memeing its oppressor, when in reality it is the one controlling the arrests, the cameras, and the accounts. Ridicule from below is a challenge; ridicule from above is a warning shot. It tells every future Nekima Levy Armstrong that the government reserves the right not just to take your liberty, but to re‑edit your dignity into content.

What makes the professional response so revealing is that the people obsessing over “minimize harm” are not looking at the one actor in the frame who has zero such code: the state. The SPJ Code of Ethics is explicit that journalists should never deliberately distort visual information and should treat subjects “as human beings deserving of respect,” balancing the public’s need to know against potential harm. Photojournalism trainings stress accuracy, empathy, and transparency, with horror stories about reporters who cloned out background details or staged scenes and lost their careers. Yet when the White House itself confirms that it posted a fake arrest image and waves it away as a “meme,” the ethical conversation snaps back to newsroom hygiene: corrections, labels, better vetting instead of treating the government as the most dangerous violator of the very standards journalists are drilled to uphold. If “minimize harm” only bites when a stringer moves a pixel but goes mute when an administration uses AI to re‑script a protester’s face, what you have is not a code of ethics; it is a leash on the press that politely ignores the hand doing the pulling.

The irony is that AI is not corrupting some previously noble information order; it is revealing what was always there. Give a government the ability to redraw a face in seconds and you do not create a new urge, you strip away the friction that used to slow its worst instincts. The Trump arrest fantasies, the doctored protest photo, the “memes will continue” defense: all of them are less about technology than about character, showing you who reaches for humiliation the second the cost of cruelty drops to near zero. That is why the usual “be careful, don’t be fooled by fakes” sermon misses the point: AI is not just a test of media literacy, it is a test of motive, and the people failing it most spectacularly are not the kids making memes, but the institutions pretending to be their victims while quietly copying their tactics.